| A culture of wellness exists when staff and child health and safety are valued, supported, and promoted through health & wellness programs, policies, and environment. [1] |

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

Evidence shows that experiences in childhood are extremely important for a child’s healthy development and lifelong learning. How a child develops during this time affects future cognitive, social, emotional, language, and physical development, which in turn influences school readiness and later success in life. Research on a number of adult health and medical conditions points to pre-disease pathways that have their beginnings in early and middle childhood.

During early childhood, the human brain grows to 90 percent of its adult size by age 3. Early childhood represents the period when young children reach developmental milestones that include:

All of these milestones can be significantly delayed when young children experience inadequate caregiving, environmental stressors, and other negative risk factors. These stressors and factors can affect the brain and may seriously compromise a child’s physical, social-emotional, and cognitive growth and development.

More than any other developmental periods, childhood sets the stage for:

Although young children are typically healthy, it is during this time that they are at risk for conditions such as:

While typically nonfatal, these conditions affect children, their education, their relationships with others, and the health and well-being of the adolescents and adults they will become. [5]

The keys to understanding childhood health are recognizing the important roles these periods play in adult health and well-being and focusing on conditions and illnesses that can seriously limit children’s abilities to learn, grow, play, and become healthy adults.

Prevention efforts in early and middle childhood can have lasting benefits. Emerging issues in early and middle childhood include implementing and evaluating multidisciplinary public health interventions that address social determinants of health by:

Early Childhood Development and Education

Early childhood, particularly the first 5 years of life, impacts long–term social, cognitive, emotional, and physical development. Healthy development in early childhood helps prepare children for the educational experiences of kindergarten and beyond. Early childhood development and education opportunities are affected by various environmental and social factors, including:

Early life stress and adverse events can have a lasting impact on the mental and physical health of children. Specifically, early life stress can contribute to developmental delays and poor health outcomes in the future. Stressors such as physical abuse, family instability, unsafe neighborhoods, and poverty can cause children to have inadequate coping skills, difficulty regulating emotions, and reduced social functioning compared to other children their age.

Additionally, exposure to environmental hazards, such as lead in the home, can negatively affect a child’s health and cause cognitive developmental delays. Research shows that lead exposure disproportionately affects children from minority and low–income households and can adversely affect their readiness for school.

The socioeconomic status of young children’s families and communities also significantly affects their educational outcomes. Specifically, poverty has been shown to negatively influence the academic achievement of young children. Research shows that, in their later years, children from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to need special education, repeat grades, and drop out of high school. Children from communities with higher socioeconomic status and more resources experience safer and more supportive environments and better early education programs.

The Effects of Poverty on Education

· Poor physical development and health (due to poor nutrition and lack of access to medical care)

· Challenges with concentration, memory, attentiveness, curiosity, and motivation[9] due to the chronic stress of living in poverty

· Greater risk for behavioral and emotional problems

· Exposure to environmental hazards (such as lead paint) and violence in their communities.

Two additional things that are important to note:

· This gap disproportionately affects Black and Latinx children.

Early childhood programs are a critical outlet for fostering the mental and physical development of young children. According to the Center on the Development Child at Harvard University’s A Science-Based Framework for Early Childhood Policy,

“ The principal elements that have consistently produced positive impacts include:

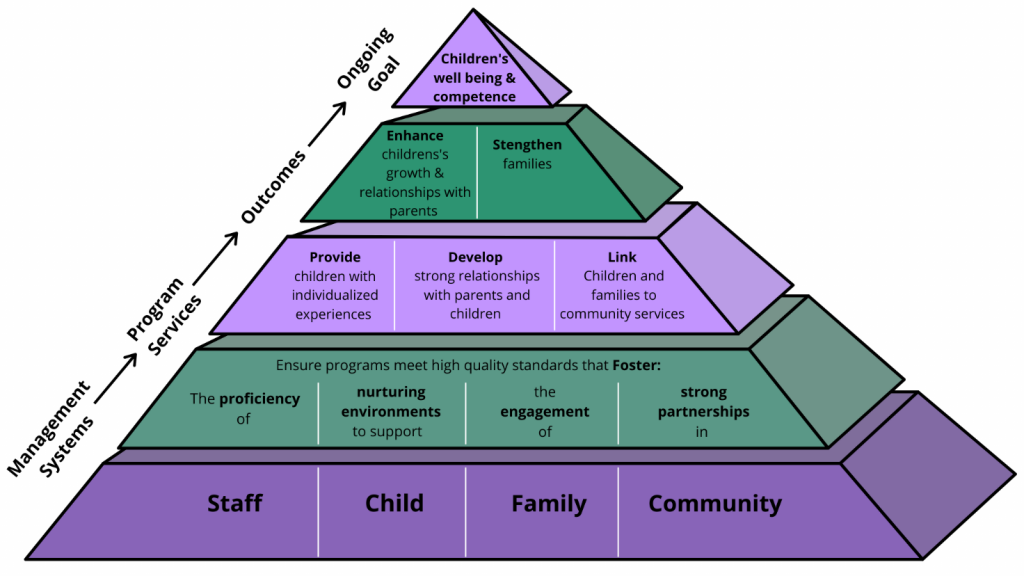

The National Association for the Education for Young Children says that high quality programs:

And you can check out the checklist 15 Must-Haves for All Child Care Programs published by The Administration for Children and Families Office of Child Care in Appendix A. What does high-quality preschool look like? Watch this 6-minute video from NPR Ed to see one example.

Early childhood development and education programs can also help reduce educational gaps. For example, Head Start is a federally funded early childhood program that provides comprehensive services for children from low–income families. Head Start aims to improve health outcomes, increase learning and social skills, and close the gap in readiness to learn for children from low–income families and at-risk children. Enrolling children in full-day kindergarten after the completion of preschool has also been shown to improve academic achievement.

Furthermore, extended early childhood programs for children up to 3rd grade, also referred to as booster programs, can provide comprehensive educational, health, and social services to complement standard early childhood and kindergarten programs. These programs help sustain and bolster early developmental and academic gains. Characteristic of such programs include:

Quality education in elementary school is necessary to reinforce early childhood interventions and prevent their positive effects from fading over time. Research also shows that school quality has an impact on both the short– and long–term educational attainment of children, as well as on their health. For example, children who enroll in low–quality schools with limited health resources, safety concerns, and low teacher support are more likely to have poorer physical and mental health.

The developmental and educational opportunities that children have access to in their early years have a lasting impact on their health as adults. The Carolina Abecedarian Project found that the children in the study who participated in a high–quality and comprehensive early childhood education program, including health care and nutritional components, were in better health than those who did not. The study found that, at age 21, the people who participated in the comprehensive early education program exhibited fewer risky health behaviors—for example, they were less likely to binge drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, and use illegal drugs. This group also self–reported better health and had a lower number of deaths.

Furthermore, by their mid–30s the children who participated in the comprehensive early childhood development and education program had a lower risk for heart disease and associated risk factors, including obesity, high blood pressure, elevated blood sugar, and high cholesterol. These studies show that quality early childhood development and education programs can play a key role in reducing risky health behaviors and preventing or delaying the onset of chronic disease in adulthood. We will look at what high quality programming looks like at the end of the chapter.

Early childhood development and education are key determinants of future health and well–being. Addressing the disparities in access to early childhood development and education opportunities can greatly bolster young children’s future health outcomes.

Additional research is needed to increase the evidence base for what can successfully impact the effects of childhood development and education on health outcomes and disparities. This additional evidence will facilitate public health efforts to address early childhood development and education as social determinants of health.[14]

Rather than waiting for health issues to arise, families and early childhood education programs should focus on supporting children’s wellness. “Wellness describes the entirety of one’s physical, emotional, and social health; this includes all aspects of functioning in the world (physiological, intellectual, social, and spiritual), as well as subjective feelings of well-being. A child who is doing well frequently experiences joy, delight, and wonder, is secure and safe in his/her family and community, and is continually expanding and deepening his/her engagement with the world around him/her.”[16]

Wellness is an active process. It requires awareness and directed, thoughtful attention to the choices we make. Early care and education programs can play a critical role in helping children, families and staff commit to and implement healthy lifestyle choices that promote both physical and mental well-being. The two, in fact, are closely linked. Our feelings, thoughts, and behaviors directly impact our physical health. Similarly, our physical health status has a direct impact on our feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.[18]

We must also support children’s mental well-being and help them navigate everyday stress and adversity as well as trauma and significant sources of stress. The American Psychological Association shares that “[b]uilding resilience — the ability to adapt well to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress — can help our children manage stress and feelings of anxiety and uncertainty.”[19]

It is important that children are in an environment that keeps them physically and emotionally safe and healthy and provides sound nutrition. As an early educator, providing these requires attention, planning, and intention.

This book is divided into three sections. These include:

Children are curious and eager to learn. They depend on their caregivers to keep them safe by making sure that nothing within a child’s reach can harm them. Injuries are a serious health risk to young children. But most injuries are predictable and preventable.[20]

ECE programs can prevent risks and unnecessary harm to children by committing to a culture of safety. A culture of safety prioritizes safety at all levels. It encourages programs to learn from past problems and prevent them in the future. [22] Programs should not assume that nothing will ever go wrong. In fact, they should plan that something is going to go wrong. And their goal is to make it as hard as possible for things to go wrong. [23]

Chapters 2 through 5 will focus on ways programs can protect children’s safety.

“Health is more than merely the absence of disease—it is an evolving human resource that helps children and adults adapt to the challenges of everyday life, resist infections, cope with adversity, feel a sense of personal well-being, and interact with their surroundings in ways that promote successful development.”[24]

As mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, research is showing that many adult health issues, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes, are linked to what happens during early childhood (and even prenatally!). We also know that during early childhood there are biological systems that are more sensitive to environmental factors (such as child maltreatment, malnutrition, and recurring issues to infectious disease).[26]

It is vital for children and their families to have support for children’s physical, oral, and mental health. This happens through promoting health and protection from illness.

Chapters 7 through 11 focus on children’s health.

Healthy eating and being active are essential to a child’s well-being. Children who are under- or over-nourished are at risk for chronic health problems.[27] Early childhood is an important time for developing healthy habits for life. Children’s bodies grow and develop in ways that affect the way they think, eat, and behave.[28]

A healthy diet not only affects growth, but also immunity, intellectual capabilities, and emotional well-being. Families and educators must ensure that children receive an adequate amount of needed nutrients to provide a strong foundation for the rest of their lives.[29]

Chapters 12 through 15 focus on nutrition for children.

Licensing for child care programs in the state of Minnesota is overseen by the Licensing Division of the Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS), whose primary mission is to ensure the health and safety of all children enrolled in licensed child care facilities in Minnesota.

Licensing oversees the operation of licensed child care facilities in child care centers (Rule 3) and family child care homes (Rule 2). By definition, both types of child care facilities provide nonmedical, age-appropriate care and supervision of infant to school-age children for less than 24 consecutive hours at a time.

Child care centers provide care in a large-group setting, usually operate in an institutional or commercial building, and must meet a number of requirements regarding their physical facilities, and the services they provide. For the most part, when this book refers to licensing requirements, it will be referencing licensing for child care centers.

Family child care homes provide care in small-group settings in the licensee’s private house or apartment. They include three types of facilities: A) Family Child Care, B) Specialized Infant and Toddler Family Child Care and C) Group Family Child Care.

Depending on the type of license, the maximum number of children who can be in care is 10-14 children (10 years and younger) at any one time. The key to licensing’s effort to protect the health and safety of children in child care is a thorough licensing and inspection program that ensures all facilities are in compliance. DHS Licensing is mandated by law to ensure that licensed facilities meet established health and safety standards and that the licensee has access to all relevant information about the department.

The Department of Human Services (DHS) Licensing Division has a critical role in monitoring and supporting health and safety in approximately 10,600 licensed child care programs in Minnesota. Licensure provides the necessary oversight mechanisms to ensure child care is provided in a healthy and safe environment, provided by qualified people, and can meet the developmental needs of all children in care. Once a facility meets all the requirements to obtain a license, licensing’s principal way of helping facilities maintain compliance is through annual site visits by licensing inspectors. In addition to conducting these inspections, our licensors work with licensees to address any needed changes, and conduct follow-up visits to confirm that problems have been eliminated. It is also the role of the licensor to investigate any complaints about a facility and consult with licensees to ensure they are aware of their rights and responsibilities.

DHS licensors work with child care centers on an ongoing basis to provide assistance and answer questions. DHS staff also provide substantial technical assistance (TA) to county licensors throughout the year. They serve as a link between licensing and the community of licensees, provide information about licensed child care to families and the public, act as a liaison with businesses, child care organizations, and resource and referral agencies, and coordinate complaints and concerns on behalf of children in care. As a result, licensing is both an enforcement agency and a resource on health and safety requirements.[31]

The complete licensing regulations, often referred to as Rule 2 (family child care) or Rule 3 (child care centers), can be found on the Licensing Division of the Minnesota Department of Human Services Child Care Regulations webpage (see Resources for Further Exploration). Highlights of the regulations can be found in Appendix B.

There are more stringent requirements for child care centers than family child care homes. The most notable difference is stricter adult-to-child ratios and staff qualifications. See Table 1.1 for a comparison of ratios.[32] The required levels of staff qualifications are also different.

Table 1.1 – Rule 2 and Rule 3 Adult to Child Ratio Comparison [33],[34],[35]

| Age Group | Rule 3 | Rule 2 |

| Infants | 1 adult to 4 children | 1 adult to 2 children* |

| Toddlers | 1 adult to 7 children | 1 adult to 3 children* |

| Preschoolers | 1 adult to 10 children | 1 adult to 6 children* |

| School-Aged | 1 adult to 15 children | 1 adult to 10 children* |

* Because the age groups are combined in family child care, the ratio cannot exceed these numbers, for a maximum/total capacity of 10 children.

While not legal regulations, there are even further requirements in place for programs that choose to pursue voluntary accreditation by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. One of the differences you will notice between licensing and accreditation is some levels of staff qualifications. See Table 1.2 for a comparison of staff qualifications.

Table 1.2 – Staff Qualifications Comparison [36],[37],[38],[39]

Teachers’ Aides and Assistants

| Rule 2 | Must be at least 18 years old. (Helpers can be 13-18 years old). |

| Rule 3 | Aide: Must be at least 16 years old, must be directly supervised at all times. |

Teacher

| Rule 2 | Must be at least 18 years old and have required health and safety training. |

| Rule 3 | Teacher: Must have 16 ECE college credits or equivalent and 1 year experience. |

| NAEYC Accreditation | A minimum of higher education degree in early childhood education, child development, elementary education, or early childhood special education or 60 units with 30 units in early childhood education, child development, elementary education, and/ or early childhood special education. (preferred accredited higher education institutions). |

Director/Administrator

| Rule 2 | Must be at least 18 years old and have required health and safety training. |

| Rule 3 | Must be at least 18 years old, high school graduate, 6 ECE college credits or equivalent and 6 months experience. |

| NAEYC Accreditation | A minimum of a baccalaureate-level higher education degree in early childhood education, child development, elementary education, or early childhood special education; or 120 college units with 36 units in early childhood education, child development, elementary education, and/or early childhood special education. |

While licensing regulations ensure that children stay safe and healthy, high quality care goes even further to provide the best start for young children. One reason that programs choose to become NAEYC accredited is to document the quality of care and education they provide children and families they serve. There are other processes and assessments that programs may use to ensure high quality, as well. In Minnesota, that includes the Parent Aware Quality Rating and Improvement System. This is a voluntary program that helps families find quality child care and early education and helps early learning programs improve their practices in order to prepare the children for school and life.

Pause to Reflect

| As you progress through this book and course, what connections can you make about how being knowledgeable about health, safety, and nutrition will support early childhood educators in both following licensing and other applicable regulations and ensuring they provide high quality care for young children and their families? |

Early childhood is a critical time in development. Many outcomes, both positive and negative, have their beginnings in these years. It is vital that children’s health and safety be protected. High-quality early care and education programs can play a valuable role in improving outcomes for children.

Chapter 1 Review